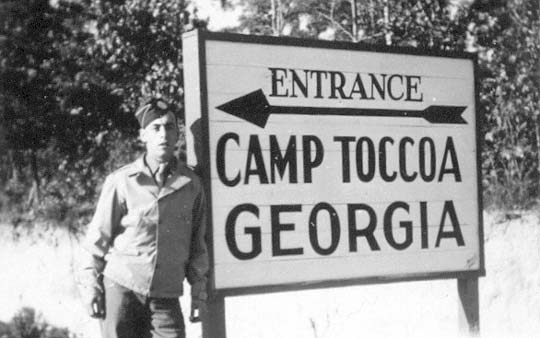

With America officially at war, in 1942 the country's military leadership began to accelerate the training of their still very new parachute troops. And Camp Toccoa, Georgia, now made famous by the HBO miniseries "Band of Brothers", played an important role in that effort.

With America officially at war, in 1942 the country's military leadership began to accelerate the training of their still very new parachute troops. And Camp Toccoa, Georgia, now made famous by the HBO miniseries "Band of Brothers", played an important role in that effort.

While Toccoa was, by comparison, a “little camp outside a little town far off the beaten path", over 18,000 young men and officers would train there and go on to fight overseas in northern AND southern France, in Holland, and at the Battle of the Bulge then "liberate" Hitler's Kehlsteinhaus, or Eagle's Nest, and then march down Pennsylvania Avenue after the war was over "over there".

At least, that is the limit to what most airborne enthusiasts and even some historians believe to be the case. Far too often the story of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment is overlooked or forgotten although it was the third of the four regiments (the 506th, 501st, 511th and 517th in that order) that formed at Camp Toccoa. Like all original Toccoa-men, the 511th cut its teeth (and "sweat blood") on the area's famous Currahee Mountain before, according to its future commander Colonel Edward H. Lahti, going on to create a "record unmatched in history".

But it is a record that most people know nothing about and it is of no surprise that my grandfather, 1st Lieutenant Andrew Carrico, III disliked most history books on the war since his beloved 511th PIR was hardly covered, if it was mentioned at all. His was a common sentiment among the "old troopers" of the 511th, and the 11th Airborne Division to which they belonged, a feeling of resentment they griped about at post-war regimental reunions for decades as attested to by my grandmother, Jane Carrico. Jane is a proud "Angelette" who became dear friends with many troopers and their wives and continues to champion the cause of the mighty 511th even after most of its men have made "the final jump."

With countless Hollywood movies, documentaries, television series, magazines articles, blog posts, podcasts and books dedicated to the 82nd (517th PIR), 101st (501st & 506th PIRs) and 17th Airborne Divisions (517th PIR), the question many 11th Airborne Division troopers painfully had for the remainder of their lives was: What about us?

Colonel Orin D. "Hard Rock" Haugen

While this website and the newly-published book When Angels Fall: The 511th PIR in World War II is dedicated to telling the story of the 511th PIR and 11th Airborne, let us cover a little of their history by traveling back to December of 1942.

While this website and the newly-published book When Angels Fall: The 511th PIR in World War II is dedicated to telling the story of the 511th PIR and 11th Airborne, let us cover a little of their history by traveling back to December of 1942.

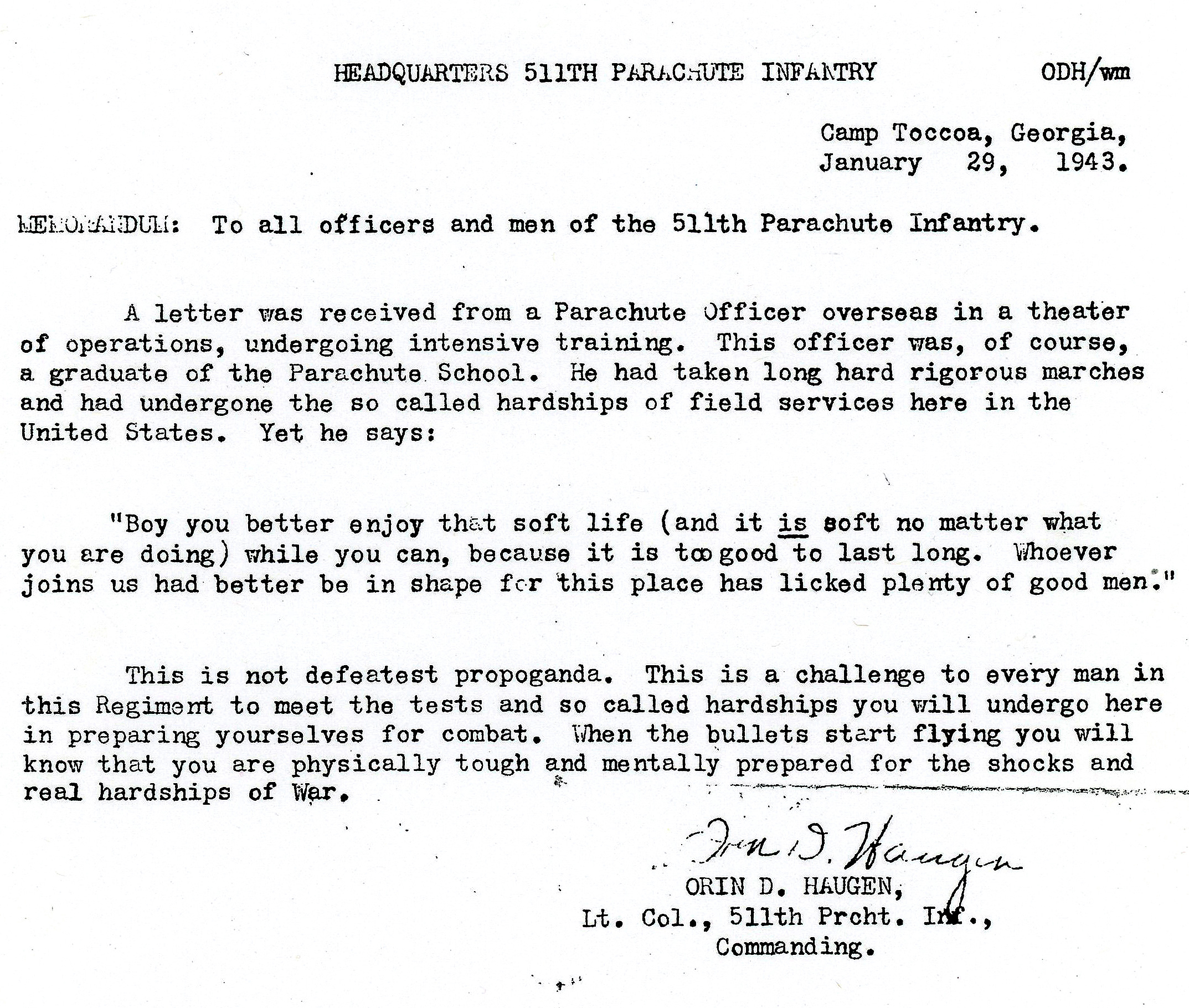

Headquartered at Camp Mackall, North Carolina, America's still-fresh Airborne Command had just approved the formation of the country's newest parachute regiment under the command of Colonel Orin D. "Hard Rock" Haugen. As one of America's most experienced parachute officers (he earned his jump wings in November of 1940), Haugen was perfect for the job. He was tough, but fair, competitive and aggressive and had high expectations, something his regiment grumbled about during training, but praised his name for once they entered combat. While it had nearly killed them at Camp Toccoa, then later Camps Mackall, Polk and Stoneman, Hard Rock's training kept them alive in the jungles, mountains and streets of the South Pacific.

On January 29, 1943 Hard Rock wrote to his men, “When the bullets start flying you will know that you are physically tough and mentally prepared for the shocks and real hardships of War.”

Perhaps that is why one of the first orders Hard Rock gave at Camp Toccoa was to have supply officers purchase boxing gloves. Having been bullied terribly when he was younger, Orin wanted his men to learn to stand and fight with confidence, first against each other then against the enemy. It is no wonder, then, that General Walter C. Krueger, commander of US Sixth Army of which the 511th PIR would be part on Luzon, said that Hard Rock's men were "the God-damned fightingest outfit I have ever seen!"

Having run cross-country at West Point (Class of 1930) and played polo for the Army internationally, Orin planned to push his men hard, especially up and down Currahee Mountain which he felt was the perfect training locale for his new regiment (he believed his unit would quickly be shipped overseas to help invade Europe). When he met a small group of officers at the Toccoa train station (now the wonderful Currahee Military Museum) before Christmas, Hard Rock promptly marched them up Currahee in their Pink and Green uniforms, stating, "You guys are going to run this everyday."

2LT Stephen "Rusty" Cavanaugh was one of the first officers to arrive to the regiment at Fort Benning's "Frying Pan" area before transferring to Camp Toccoa. Rusty, who later served as Chief SOG in Vietnam, remembers watching Hard Rock soak his feet in alum solution to toughen them up for their daily runs which Colonel Haugen often led. Cavanaugh added that the men took to calling their chain-smoking regimental commander "The Great Stone Face" because he rarely smiled, "but never to his face" Rusty said with a chuckle.

2LT Stephen "Rusty" Cavanaugh was one of the first officers to arrive to the regiment at Fort Benning's "Frying Pan" area before transferring to Camp Toccoa. Rusty, who later served as Chief SOG in Vietnam, remembers watching Hard Rock soak his feet in alum solution to toughen them up for their daily runs which Colonel Haugen often led. Cavanaugh added that the men took to calling their chain-smoking regimental commander "The Great Stone Face" because he rarely smiled, "but never to his face" Rusty said with a chuckle.

Although he rarely showed it, the Great Stone Face truly cared for his regiment and taught his officers that they should always put the welfare of their men foremost and to lead by example. Officers were to jump out the door first, eat last, share the load by occasionally carrying machine guns or mortar tubes on marches and check their men’s feet for blisters.

As Hard Rock's wife Marion told their son William (whom the paratroopers nicknamed "Pebble"), "He never asks the men to do something he isn't willing to do himself."

Camp Toccoa, GA

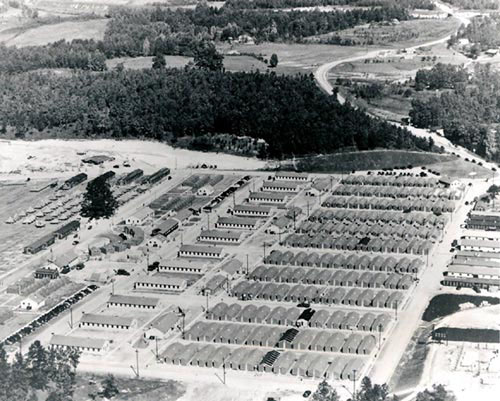

On January 5, 1943 Colonel Haugen's 511th PIR officially activated at Camp Toccoa and as volunteers for parachute duty began to roll in on trains, they were greeted by the booming voices of sergeants who hounded them off the train and into waiting trucks which brought them to the chilly and still-under-construction camp.

On January 5, 1943 Colonel Haugen's 511th PIR officially activated at Camp Toccoa and as volunteers for parachute duty began to roll in on trains, they were greeted by the booming voices of sergeants who hounded them off the train and into waiting trucks which brought them to the chilly and still-under-construction camp.

Pvt. Billy Pettit remembers everyone tossing their barracks bag over the truck’s side only to watch them splash into Georgia’s ankle-deep mud. Billy then dropped off the truck and felt mud ooze into his shoes.

He told me that one new arrival saw the red Georgia mud and mistook it for blood. That same mud would be frozen when the men woke up, turn into a quagmire during the day only to freeze again at night (along with the cold, exhausted recruits).

“By this time, being a paratrooper didn’t seem to be a glamorous as had been previously presented,” Billy said.

After they "settled in" to their tents in the muddy waste known as "W" Company, or Cow Company, the men were marched in front of a selection committee (wearing only their underwear) consisting of the regiment's battalion and company commanders and other senior officers. Colonel Haugen ordered his leadership to interview each man and look for athleticism, confidence, a willingness to try and intelligence.

Many Angels attested that attitude was the first qualification for the regiment. When Col. Haugen personally interviewed Donald “DJ” Hyatt and his friend, the colonel asked DJ’s friend if he could do twenty-four pushups. He responded, “No, sir.”

Hard Rock then turned to Hyatt and asked the same question. “I don’t know, sir, but I’ll try,” DJ replied.

DJ’s willingness to try led to his acceptance; his friend was rejected.

The volunteers also had to make it up Currahee then pass a flight physical and color blindness tests (paratroopers needed to distinguish between red and green jump lights and set up colored signaling panels). They also had to earn a score of 110 or higher on the Army’s General Classification Test (AGCT), the same requirement for Officer Candidate School (OCS). As one trooper later put it, the 511th was looking for men smart enough to lead, but dumb enough to jump out of an airplane.

Hard Rock's tough conditions were hard to meet and out of 12,000 men who volunteered for the 511th PIR, only 3,000 were accepted (this number would soon drop to the T/O's 2,200). This washout rate led the War Department to censure Colonel Haugen, saying his requirements were too stringent. Hard Rock just laughed and said "they were too late!" Those who remained were the creme de la creme and they WANTED to stay, one of the most important characteristics within a parachute unit. Volunteers who failed to impress the selection committee or make it up Currahee went back to their watery tent in Cow Company and were transferred out of the camp within a few days.

Life in Camp

After moving into sixteen-man hutments, the 3,000 "Jockos" (parachute trainees) who made Hard Rock's cut were now under the control of the 511th’s elite cadre which Col. Haugen and his Executive Officer Maj. Glen McGowan of Chicago, Illinois, handpicked from the 505th, 502nd and 503rd PIRs and 504th PIB. The cadre immediately began a training program that was a mixture of Basic Training and a primer for the parachutes.

After moving into sixteen-man hutments, the 3,000 "Jockos" (parachute trainees) who made Hard Rock's cut were now under the control of the 511th’s elite cadre which Col. Haugen and his Executive Officer Maj. Glen McGowan of Chicago, Illinois, handpicked from the 505th, 502nd and 503rd PIRs and 504th PIB. The cadre immediately began a training program that was a mixture of Basic Training and a primer for the parachutes.

And it was designed to be tough. As acting-Sergeant Robert R. Kennedy announced, the regiment planned to only accept 30% of the new “Jockos” and of those, 25% would quit before the regiment headed to Fort Benning’s jump school.

G Company's 2LT William L. Miley, whose father was the famous General William Miley who commanded the 17th Airborne Division at the time, told a group of recruits, "When you guys become troopers, you'll own the world and you'll never let things stand in your way."

After breakfast (meals were served "family style" and seconds were given without question) the recruits' physical training (PT) began with the Daily/Army Dozen in the frozen Georgia mud (which turned to sludge during the day): side benders, toe touches, side straddle hops, windmills, squat thrusts, six-inch leg lifts, flutter kicks, crunches, lunges, knee bends, eight-count pushups, and jogging in place (some recruits and platoons began the day by running around the camp). It was not uncommon for units to repeat the Daily Dozen several times and since the 511th was at Toccoa just after New Year’s they often had to perform PT in the mud in cold temperatures, complete with bone-chilling winds and the occasional icy rain.

In addition to the 40-foot climbing rope, it was "double quick" everywhere and pushups were a way of life in what one trooper described as elbow-deep mud, but there was a method to the madness. Standard doctrine at the time stated that paratroopers needed to be in elite shape to handle the physical requirements of jumping from an airplane, including the opening shock and landing, then the expected rigors of combat. As such, Camp Toccoa was a blur of physical training with the cadre embracing the motto of, "Run ‘em until they think they can’t go another step, then run ‘em five more miles just to prove they can.”

To encourage his men during especially difficult exercises, the famous Col. Robert Sink of the 506th PIR shouted to his own men at Toccoa, “We want the best!” (Sink would later command the 11th Airborne from 1951-1953). Not to be outdone, Col. Haugen bellowed to his 511th, “We are the best!”

And since the 511th was at Toccoa just after New Year’s they often had to perform PT in the mud in cold temperatures, complete with bone-chilling winds and the occasional icy rain.

“The rain was awful,” Pvt. Billy Pettit noted. “It was never quite freezing, but there was mud up to your ankles everywhere.”

Afternoons were usually spent training for parachute deployment beginning with the boxy mockups of C-47 fuselages where the men divided into “sticks” of 16. There training officers taught recruits how to sit on the benches and listen for commands to “Stand up!” “Hook up!” “Equipment check!” “Stand in the door!” “Go, go, go!” The men learned to plant their left foot and pivot out the door with their right, thus allowing their backs to take the brunt of their aircraft’s propwash. The jumper would then count “one-thousand, two-thousand, three-thousand!” at which point either the static line would deploy their canopy, or they would tug the handle for the reserve chute on their chest.

After fuselage training, the 511th’s Jockos quick-timed to a collection of five-foot high platforms where they practiced landing in sawdust pits or over to the loathed “nut-crackers” where they hung in parachute harnesses to practice “slipping” by pulling on the risers. Slipping changes the canopy’s shape which provides a paratrooper a small amount of “steering” in the air. It was a necessary skill to acquire, but an uncomfortable way to learn it.

"You better get your family jewels in the right place," laughed D Company's Private Billy "The Kid" Pettit, who at seventeen was the youngest man in Hard Rock's regiment.

Next the men quick-timed over to a 34-foot jump tower, “the widow maker” or “the great separator”. My grandfather, Dog Company’s 1LT Andrew Carrico, pointed out that this tower washed out more recruits than any other exercise as after climbing the stairs and hooking their harness onto a pulley, the men could look down to see a the tiny speck of a mess kit placed there for depth perception. The Jockos then performed a “leap of faith” out the “door” before sliding down a 200-foot cable.

Next the men quick-timed over to a 34-foot jump tower, “the widow maker” or “the great separator”. My grandfather, Dog Company’s 1LT Andrew Carrico, pointed out that this tower washed out more recruits than any other exercise as after climbing the stairs and hooking their harness onto a pulley, the men could look down to see a the tiny speck of a mess kit placed there for depth perception. The Jockos then performed a “leap of faith” out the “door” before sliding down a 200-foot cable.

When not in PT or jump training preparation, the men were subject to frequent lectures on a never-ending list of subjects relating to military life and protocols before running through the camp’s challenging obstacle course or participating in the ever-present close order drill. The day ended with the Buglers’ Regimental Retreat Formation followed by evening chow before lights out.

Cpl. Murray Hale recalled, “These were tough and impressionable days. And a fitting introduction to our forthcoming basic training to become troopers of the 511th...”

Saturday afternoons were spent in parade review on the athletic grounds, after which most of the 511th had the rest of the weekend off. Those very few who were lucky enough to get passes ventured into nearby Gainesville or even Atlanta (especially Peachtree Avenue), while others stayed in camp to enjoy the peace and quiet (and extra helpings of dessert). The enlisted men enjoyed beers at John Lathan’s Wagon Wheel right outside the camp’s gate while the officers preferred the Hi-De-Ho closer to town.

Their routine changed little until on March 21, 1943, seventy-five days after the 511th was activated, the last elements of the fully formed regiment boarded a train for Camp Mackall, NC., Airborne Command’s new headquarters.

Col. Haugen’s men were headed to join Major-General Joseph May Swing's 11th Airborne Division, the Angels, of whom General Robert L. Eichelberger, commander of the U.S. Eighth Army, later declared "No one could have asked for finer fighting men."

To learn more about this historic regiment and the intrepid men who fought in it, you can order Jeremy C. Holm's new book, WHEN ANGELS FALL: From Toccoa to Tokyo, The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II by visiting our online store or purchasing a copy wherever books are sold.