Pfc. Swan, Harry A.

Company G, 511 PIR + Runner, 11th Airborne Honor Guard for Gen. Douglas MacArthur

03/13/21 - 09/10/07 (Age 86) - gravesite

Citations: Silver Star, Combat Infantryman Badge, Purple Heart, Presidential Unit Citation, World War II Victory Medal, Philippine Presidential Unit Citation Badge, Philippine Liberation Medal with service star, the American Defense Medal, and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with three Battle Stars and one Arrowhead

Locations: Camp Mackall, Camp Polk, Camp Stoneman, New Guinea, Leyte, Luzon, Japan

Harry Swan was born in Passaic, New Jersey, on March 13, 1921, and he grew up there. Harry was inducted into the Army at Newark on February 20, 1943. He stood six-foot-two, weighed in at 195 pounds, and was a “hard as nails” twenty-one-year-old. The Army thought Harry would make a good paratrooper so he volunteered for parachute duty. Harry soon found himself in training at Camp McCall, North Carolina in Company G of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 11th Airborne Division. The paratroops were considered experimental until 1941, so the “Airborne” was still very much in its infancy at that time.

The 511th PIR shipped out for the Pacific Theatre on May 8, 1944 onboard the SS Sea Pike, a ship which the paratroopers came to detest on their voyage. The 11th Airborne landed in New Guinea where the Angels spent five months undergoing theatre training. Beginning on November 23, 1944, the paratroopers spent a month in the jungles and hills of Leyte where they engaged and destroyed the enemy in brutal combat. During this campaign, Harry and G Company helped rescue a surrounded C Company and Regimental HQ who had been cut off and fought the enemy for three days.

When Harry and G Company arrived, he noted that the men they were rescuing "were in a deplorable condition, both physically and mentally, having survived numerous banzai attacks.”

Harry and the 511th then made a combat parachute jump onto Tagaytay Ridge outside Manila on Luzon on February 3, 1945, then the regiment force-marched 32 miles to the southern approaches of Manila. Harry's G Company was involved with the difficult assaults on the Japanese's Genko Line defenses before they locked in close combat with the enemy near Nichols Field. Pfc. Harry Swan would receive the Silver Star for gallantry during an action on February 5th (see citation below). He was then wounded in action during the morning of the next day; and then wounded again that afternoon, only this time more seriously. Harry was medically evacuated and hospitalized at Biak, Netherland East Indies.

Harry's Commendation for the Silver Star:

Department of the Army, General Orders No. 14 (June 25, 1979)

Private First Class Harry A. Swan distinguished himself by gallantry in action against the enemy near Nichols Field, Manila, Luzon, Philippines Islands on 5 February 1945. When his company was pinned down by heavy enemy machine gun fire, the Company Commander (Captain Patrick W. Wheeler) ordered a machine gun into a forward position to attempt to silence this deadly fire. In moving forward both the gunner and assistant gunner were disabled. Private First Class Swan voluntarily and with complete disregard for his own safety ran forward while constantly exposed to heavy enemy fire; picked up the tripod and moved it to a favorable firing position. This gallant soldier then ran back still under heavy fire; retrieved the machine gun and placed it on the tripod. At this time he noticed that the ammunition belt was covered with mud. He called for ammunition to be brought up but received no response. For the second time, Private First Class Swan ran back through the heavy enemy fire; obtained a box of ammunition; ran forward for the third time; loaded the machine gun and began firing. His accurate fire destroyed the enemy machine gun which allowed his company to proceed on its vital mission against the highly defended GENKO LINE. Private First Class Swan's outstanding bravery, daring initiative, and sincere devotion to duty reflect great credit upon himself and exemplifies the highest traditions of the Armed Forces of the United States.

Now, you'll notice that the award was given on June 25, 1979, decades after the war ended. Harry's buddies often asked him at regimental and division reunions if he had ever received his commendation and were shocked when the veteran trooper, now a police officer in New Jersey, said, "No."

The main reason for this delay is that while G Company's Captain Patrick Wheeler, who watched Harry's courageous actions that day, promised to put the young paratrooper in for the Silver Star, Captain Wheeler would be tragically killed later that very day. When Harry's buddies learned this at the unit reunions, in the 1970's they took it upon themselves to get their buddy the recognition he deserved. They even talked to the 11th Airborne Division's former commanding general, Major General Joseph May Swing who said he remembered reading the account of Harry's bravery on Nichols Field in a report and that he would support their efforts to get Private First Class Harry A. Swan his well-deserved commendation. The rest, as you can see above, is history.

Following his hospitalization in February of 1945, Harry returned to G Company before the surrender of Japan. He was then selected for the “Honor Guard Platoon” that accompanied General Douglas MacArthur when he first went into Japan, and that was quite a high honor considering all the top notch manpower the general had available to choose from. Harry’s photograph and an announcement to that effect made Page #1 news in his hometown paper, The Herald News, back in Passaic, NJ. The Honor Guard was flown to Okinawa for special training, then on August 30, 1945 the platoon flew to the Atsugi Airstrip, making them some of the first Allied troops to land on Japan. General MacArthur arrived two hours later on his aircraft, The Bataan, and was escorted to the New Grand Hotel in Yokohama. The Honor Guard Platoon then guarded all the ranking allied officers who stayed at the hotel. Then on September 2nd, Harry and the rest of the Honor Guard Platoon escorted General MacArthur to the USS Missouri for the surrender ceremony.

During the early days of the occupation of Japan, one morning when Harry was standing guard a Filipino man named Felipe recognized him from an incident some months earlier when the 511th PIR was in Manila. It happened one evening when Harry was walking alone down one of the narrow Manila streets when he came upon three American G.I.’s in the process of beating up one of the locals, a much smaller man. Well, that just didn’t look right to the tough New Jersian.

Now you have to understand that Harry was always a fighter: when he was a kid, certainly as a paratrooper, and even later in life, Harry never ducked a fist fight. And so, like a Guardian Angel, Pfc. Swan growled at the offending soldiers, "You want to fight someone? Fight me!" Realizing they now had a real problem on their hands, the trio promptly hightailed it to safer quarters. Harry then assisted their victim who turned out to be Felipe, the same Felipe who recognized Harry when he was standing guard outside the New Yokohama Hotel.

Felipe was now one of General MacArthur’s kitchen staff, a cook that the general had brought along to Japan. From that point on, Harry was invited to come around to the kitchen anytime and receive the same meals served at the General’s table. Harry took him up on the offer and he ate pretty well for a time, certainly much better than the “10 in 1” rations that the other 511th troops were eating at the time. But, that situation only lasted until October when Harry and the Honor Guard members were sent back to their original companies.

I suspect that Felipe was somehow involved in the paratroopers' theft of General Douglas MacArthur's private stores in September of 1945. After MacArthur’ moved to Tokyo, his 11th Airborne Honor Guard was relieved, but before being released the paratroopers were given one last Yokohama task: help load the general’s food stores and kitchen. After MacArthur’s chef,whom I believe was Felipe himself, pulled a truck up to the New Grand Hotel. Harry and his fellow Angels then carried out boxes of Campbell’s soup, caviar, sausages, vegetables and other foods they had not seen in over a year. While the mess sergeant directed them to load boxes, he failed to notice the resourceful Angels “liberating” several crates by passing MacArthur’s stores over the side to their comrades.

Then comes another of Harry’s interesting stories, told in his own words:

The "Chocolate" Occupation of Japan, 1945:

When I reported back to my unit, Company G, 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, on October 3, 1945. The Company Commander, Captain (John J.) Starr, immediately assigned me to a new mission. The Captain told me to assemble a 12-man squad to carry a truckload of boxes of chocolate, he would provide the truck and driver. There was a small village about 45 kilometers northwest of our Headquarters. The Japanese people living there, we were told, would not leave their homes. They feared they would be harmed by U.S. soldiers if they went outside. Of course this wasn't the case, we had no intention of harming anyone. We were supposed to spread the word that the war was over and that they should return to their jobs and farms, and send their children back to school. "There is peace now," was to be our message. Captain Starr said we were to explain the U.S. government would make food and medical supplies available as needed. Once we obtained their trust, we were to obtain a count of how many civilians were in the village. Then we were to take the boxes of chocolate and give each person a Hershey bar. When we got under way, we all wondered what was going to happen. Upon our arrival, all was quiet; there was absolutely not a single person anywhere in sight. We started to knock on the shutters and doors, calling out our message of peace to the occupants. There was no response for about 15 minutes, then the doors and shutters on one side of the village opened and twelve men emerged, all dressed in black clothing. One man, the tallest, wore a stovepipe hat like Abe Lincoln's. He said, "My name is Toyacowa. I am mayor of this village. How many hostages will be needed?"

We were surprised; in fact, shocked. We calmed him down and told him, "Mayor, we don't want to take hostages. We are American soldiers and hostages are not needed for us to be friends again. Return to your jobs, your farms and your schools. That is what we want." The mayor was elated and he and all around him were raised in spirits. Fortunately for all of us, the mayor spoke almost perfect English. After the word spread throughout the village, the town square filled with Japanese civilians, young and old. I guess there must have been four or five hundred altogether. Then, out came the Hershey bars. We handed the chocolate to those assembled and then we told the mayor to distribute the rest throughout the village. They did so. We left the open boxes on the ground. You should have seen their faces in delight. I don't believe many had ever eaten chocolate before, but they were making up for lost time.

After departing the village and giving our report to Captain Starr, the Army sent in more supplies to these poor, hungry individuals who could not help that their country had been at war. The Supreme Allied Commander, General MacArthur, assured a smooth transition to peace and democracy for the Japanese by his ordering of humanitarian assistance to civilians. One thing I learned from this episode is how news travels fast. That year, I was later to travel by rail through Japanese cities. At each stop, our train would be swarmed by Japanese children all chanting the one word of English they had learned: Chocolate!

Two months after this incident, Pfc. Harry Swan returned to the United States in December of 1945. He was discharged at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey on January 9, 1946, and returned home to Passaic, NJ. He then entered a long career on the Passaic police force and retired as a Police Captain. He and his wife Marilyn then moved to Austin, Texas to live in retirement near their daughter.

OBITUARY - 09/10/07:

Retired Passaic, New Jersey, Police Captain and U.S. Army Silver Star recipient Harry Anthony Swan, 86, the father of the New York Daily News online entertainment editor Lisa Swan, died peacefully at his home in Austin, Texas, of natural causes Monday. At Swan's side was his wife of 52 years, the former Marilyn Wells. The World War II veteran was born in Passaic on March 13, 1921, the second of 14 children. During the war, his unit, G Company, 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, engaged in ferocious action in battles in the Pacific. His awards include the Silver Star, Bronze Star and Purple Heart medals and the Combat Infantry Badge. When the Japanese surrendered in August 1945, Army General Douglas MacArthur selected Swan for his Honor Guard. Swan served with distinction for 34 years as a Passaic police officer. In 1961, then-New Jersey Governor Robert Meyner awarded Swan the New Jersey Valor Award for rescuing 27 families from a tenement fire in Passaic. Besides his wife and daughter Lisa, Swan is survived by two sons, Judge Michael Swan and Patrick Swan; another daughter, Karen Swan Foster, and four grandchildren.

Perhaps, outside of the stories of Harry's courage under fire, there is one that best paints the picture of what kind of great man he was. Harry's best friend in the service was Private Matthew "Matty" Pike. The two first met in Boot Camp after Matty took a big piece of cake, angering other recruits who chased Matty through the Mess Hall. Well, Matty B-Lined it for Harry's side (the two had never met before this moment). Tearing the cake in half, Matty placed half of the huge slice on the 6' 2" 190-pound Private Harry Swan's plate, then grinned at his would-be-attackers who, seeing Harry's mass, gave up the chase.

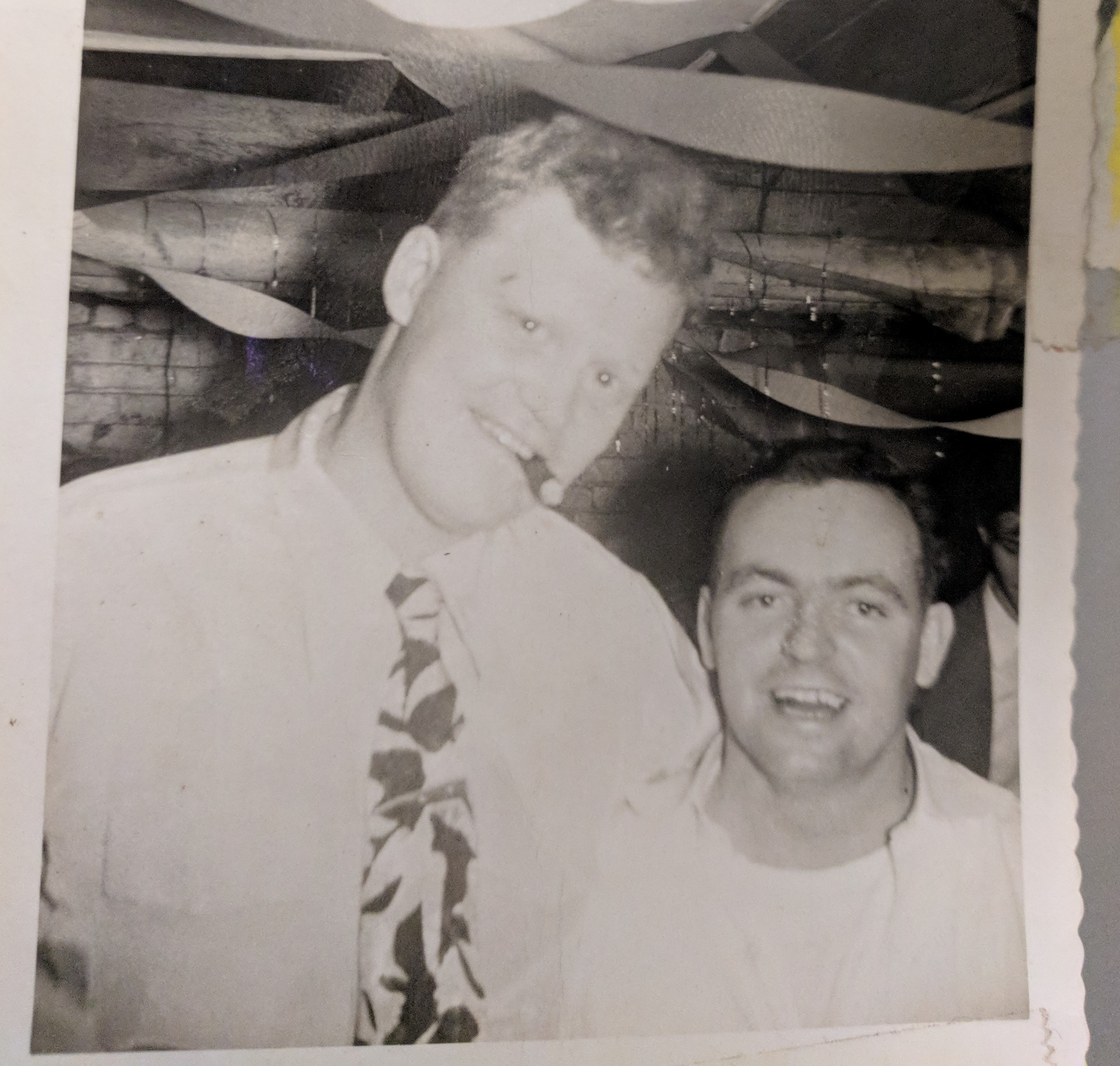

Harry and Matty saw hell together on Leyte and Luzon and remained friends for life (see their photo below; Harry on left, Matty on right). When Matty Pike died on March 24, 2008, Matty's daughter told Harry's daughter Lisa, "Lisa, in all my life, I never saw my father cry. Not when his parents died. Not in any tragedy that befell us. But when we told him Harry Swan had died, he wept like a baby."

|

To learn more about the 11th Airborne Division in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of our books on the Angels: